What is Adaptive Leadership?

Adaptive Leadership is the mobilization of people to navigate complex challenges. While the practices by which this is done are many and varied, ultimately Adaptive Leadership requires building new capacity for thought and action in individuals, organizations, or societies through the use of iterative, experimental, and contextually tailored approaches that help stakeholders learn new behaviors when they confront change and loss.

How is Adaptive Leadership Deployed?

Adaptive Leadership is a set of practices. These practices are therefore behavioral and unique to the context or situation. Thus, leading adaptively is not “one-and-done” or contingent upon positional authority, but can be practiced from any position in an organization, government, or society. It is deployed through contextually relevant interventions that help individuals make progress on complex challenges.

Ten Distinctions of Adaptive Leadership

1. Adaptive Leadership is a Set of Practices.

These practices are therefore behavioral and unique to the context or situation. Thus, leading adaptively is not “one-and-done” or contingent upon positional authority, but can be practiced from any position in an organization, government, or society. It is deployed through contextually relevant interventions that help individuals make progress on complex challenges.

2. The Practices of Adaptive Leadership are Distinct from Positional Authority.

Leadership is often confused with authority. And yet many authorities do not lead – which is to say they don’t behave in ways that help others navigate complex problems. The distinction between the behaviors of leadership and positional authority is crucial because it suggests that we are “leaders” only when we deploy agency to practice behaviors that support progress on complex adaptive problems. While authority – both formal and informal – can be valuable for focusing attention or marshaling resources, in and of itself, it does not build capacity. Likewise, fear, or excessive deference to authority, may prevent us from deploying the agency necessary to practice leadership.3. Technical Challenges are Not Adaptive Challenges.

3. Technical Challenges are Not Adaptive Challenges.

Technical challenges, like repairing a flat tire or conducting heart bypass surgery, are solvable with expertise, authority, and effective execution. Domain knowledge exists to solve them, even if they are intricate or layered problems. On the other hand, adaptive challenges, sometimes referred to as “wicked” problems, are more complex, require shifts in values, beliefs, or behaviors, cannot be solved by one person alone, and often necessitate building new capacities that did not previously exist. In short, adaptive problems require leadership. A common pitfall in organizations is to treat adaptive problems as technical problems, which often leads to repeated failure and an emotional response. In truth, many problems are a combination of both technical and adaptive elements, and discerning between these elements is essential for effective intervention and progress. Failure to address adaptive problems gives way to frustration and a cycle of repeated failure.

4. Adaptive Leadership Requires Movement Between the Dance Floor and the Balcony.

Most people stay on the “dance floor,” caught up in the day-to-day tasks and actions of execution. Adaptive leadership requires practitioners to move to the “balcony” to observe not only the human dynamics in the organizational system, but also the behavioral patterns of stakeholders, and the underlying values of factions which may have unique perspectives. Moving to the balcony is a form of structural or “systemic” listening. When we view the system from the balcony, we move away from personal interpretations, and instead, generate more insight, so that our interventions on the dance floor are more informed, and have a greater impact.

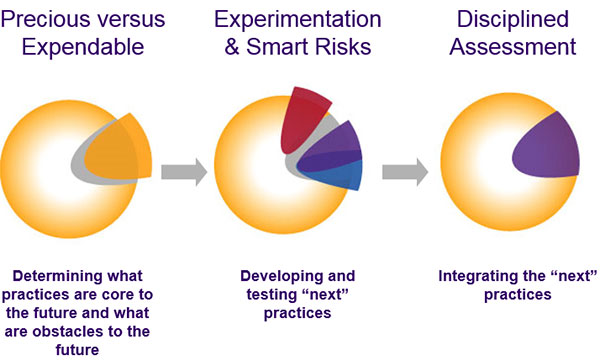

5. Adaptive Leadership Practice Requires Experimentation.

In the same way evolutionary biology suggests species changes require thousands of generations of incremental adaptation through small genetic mutations to create new capacity, so too, does adaptive leadership require incremental and subtle updates to the behavioral operating system of the individual or organization. Change requires deciding which behaviors, traditions, and values are worth keeping (most of them), which behaviors, traditions, and values need to be discarded (the small minority of them), and an experimental process to figure out which new behaviors should replace those that inhibit progress. Oftentimes, aspiring change agents push for too much change too quickly, without deeply understanding the foundational values, beliefs, or traditions of teams, cultures, or societies. Small experiments create valuable data and incremental learning.

6. Adaptive Leadership Means Stakeholders Will Need to Accept Losses.

Most of us don’t fear change if the change is positive. But some change represents loss, especially when we’re asked to discard old values, beliefs, or ways of doing things. Losses include not just the loss of material resources, but also the loss of stability, identity, competence, control, or influence. In other words, tearing our muscles (loss of comfort) is required to build new muscles. Working through these losses can be a difficult, but necessary, process for growth.

7. Anchor on Purpose to Focus Engagement and Prevent “Work Avoidance”.

Strong purpose helps us navigate loss with inspiration, energy, and focus. It helps us adapt to the difficult work of building new capacity. But when the losses we are asking others to sustain are too great, many will resist doing the real work of change either because the lift is too heavy, or the competence and know-how in the system doesn’t yet exist. In these cases, people may disengage from doing the real work, and patterns of “work avoidance” take the form of apathy, blame, scapegoating, excuses, gaslighting, violence, or any number of behaviors counter-productive to getting real work done.

8. Doing the Real Work Requires Productive Disequilibrium and a Powerful Holding Environment.

A pressure cooker can cook a roast in a fraction of the time of a standard oven. In our organizations, governments, or societies, when we create the conditions that allow for higher pressures to exist – conditions such as trust, accountability, transparency, a tolerance for learning that comes from failure, etc. – we empower others to learn and grow in highly productive ways. Acts of leadership require us to understand the temperature of the operating environment and adjust the “heat” (pressure or stress) accordingly.

9. Adaptive Leadership Work is Risky and Requires You to “Stay in the Game.”

When we ask others to adopt new ways of behaving that are uncomfortable, or for which their current competence isn’t sufficient to solve a complex problem, they may feel helpless, directionless, or resistant. In short, stakeholders are provoked because the heat gets too high. Homeostasis is disrupted. When we advocate for change that requires stakeholders to accept losses, we are often viewed as a threat to the system and can become a target for their fears and frustrations. This is why many authorities in systems are metaphorically (or literally) assassinated. A central requirement of adaptive leadership practice, therefore, is to “stay alive and stay in the game” – namely, to be a part of the system you’re trying to impact long enough to create progress.

10. Effective Adaptive Leadership Practice Requires Identifying the Real Work.

Sometimes we seek to treat the symptoms or conditions of the problem and not the underlying problem itself. Regularly asking, “What is the essential work?” will force us to explore and shift our interventions from the individual, team, and organizational level, and back again, in a dynamic, iterative process that is both probing and clarifying. The diagnostic work of understanding the real issues, problems, and opportunities is an essential practice of adaptive leadership.

So, What Do I Do?

This question is akin to asking: “As an artist, how do I create a masterpiece?” It is a broad question that cannot be directly answered when divorced from context, experience, knowledge, tools, environment, subject matter, medium, or inspiration. But here are a few generic and overarching ideas to help you begin to orient your adaptive leadership practice.

Sustain.

Stay in the game. Develop a tolerance for a higher degree of stress and ambiguity. Do the inner work that allows you to hold steady in the face of external pressure. Embrace paradox. Build the capacity to engage persistently, consistently, and with focus and intention. Deploy competence and solid judgment to build informal authority, including credibility. Resist attempts to be sidelined or taken out. Fortify yourself with purpose and self-care.

Sense-Make.

Explore the context of your situation. Listen to the song beneath the words. Understand the relationships between stakeholders by mapping out factions and stakeholders with their respective values, purposes, and potential losses. Clarify stakeholder expectations and perspectives. Do the inner work that allows you to see objectively, free from the role dynamics as a member of the system. Repeatedly diagnose the system and container. Get to the balcony to formulate an interpretation. Postulate the values and norms surrounding the problems that exist. Learn to ask who, how, what, and the why behind repeat behaviors so you can identify hidden agendas.

Navigate.

Chart a course through the elements of complexity. Refine your understanding by testing assumptions with micro-experiments. Get to the balcony to assess the impact of your experiments. Challenge the understanding of the status quo. Question the norms and traditions of those who are avoiding the essential change work. Articulate the losses. Design a holding environment that allows for failure and learning.

Activate.

Deploy experiments with detached intention for the sake of gathering more data. Name the elephants in the room. Implement conditions that strengthen the holding environment over time by raising or lowering the heat. Disrupt social and behavioral patterns of the system. Experiment with silence. Test your interpretations by sharing them. Iterate on past experiments with new knowledge. Use designed provocation to engage stakeholders and expand tolerances.

In Conclusion

Adaptive Leadership equips individuals and organizations to embrace complexity and engage others in tackling tough challenges. It’s a leadership approach that prioritizes adaptability, experimentation, and collective effort over individual heroics or rigid formulas. By focusing on the nuances of context and actively developing the people around them, practitioners of adaptive leadership help create a culture of resilience and continuous learning, ensuring that teams stay engaged and empowered to solve the problems of today while preparing for the uncertainties of tomorrow.